I’ve known Tim Burton’s work for most of my life, how could I not? His aesthetic is unmistakable. Crooked lines, pale faces, and a kind of melancholy that feels oddly comforting. Like many, his worlds have always felt familiar to me. Instantly recognizable, and comforting in the most macabre way.

But familiarity isn’t the same as understanding.

As I stood in the Design Museum’s dimly lit entrance hall to ‘The World of Tim Burton’ exhibition, I realised I knew very little about the man behind the monsters.

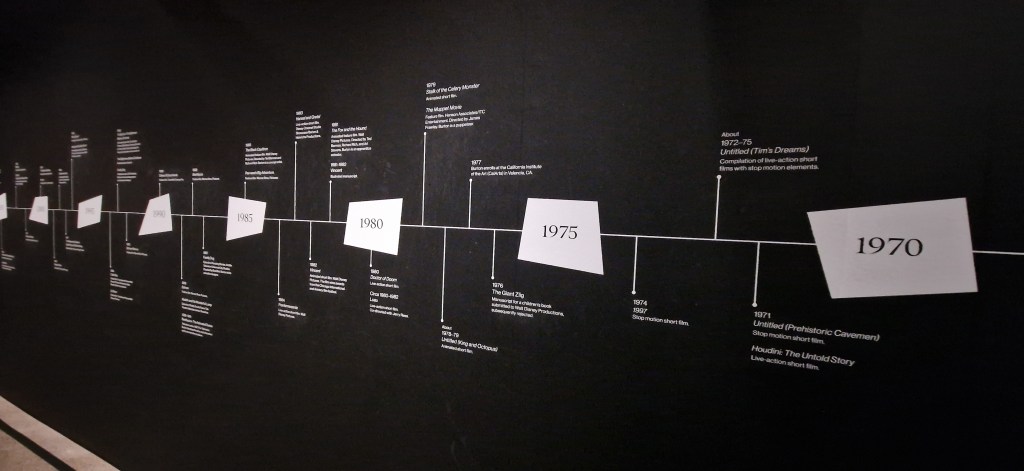

Reading through the extended timeline of creative offerings Burton has made to the film world over the decades, I felt a quiet sense of gratitude. Gratitude for living in a time where his work isn’t merely a reflection of his life, but a midway point. An unfolding archive of beautiful things yet to come.

Troubled Beginnings

I knew Tim Burton had worked closely with Disney. His fingerprints are all over the studio’s darker, more eccentric turns (and many of my personal favorites) such as Alice in Wonderland, The Nightmare Before Christmas, even the feature-length Frankenweenie. But what I didn’t know, until I stood reading the exhibition’s timeline, was how rocky that relationship had been at the start.

Fresh out of CalArts in the early 1980s, Burton was hired as an animator. But his style – strange, shadowed and even slightly macabre, clashed with Disney’s polished aesthetic. His sketches were “too weird,” his stories “too dark.” When he made the original Frankenweenie (a short film about a boy who reanimates his dead dog) Disney deemed it “too scary for children” and let him go.

Years later, Burton would reflect:

“I should have known early on that I had a troubled relationship with Disney. That should have been the first sign.”

He described the experience as:

“a mixed bag… I can acknowledge the many positives, but equally, the soul-destroying side.”

That rejection, oddly enough, became the doorway. He left the studio and began building his own house of shadows. One where the misfits had names, and the monsters were allowed to feel.

Inside the Mind: Sketches, Scribbles, and Things That Stare Back

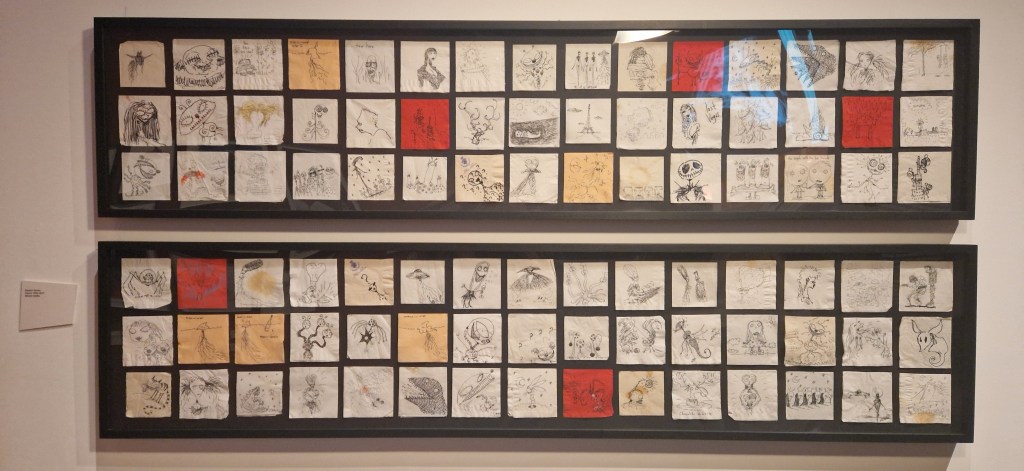

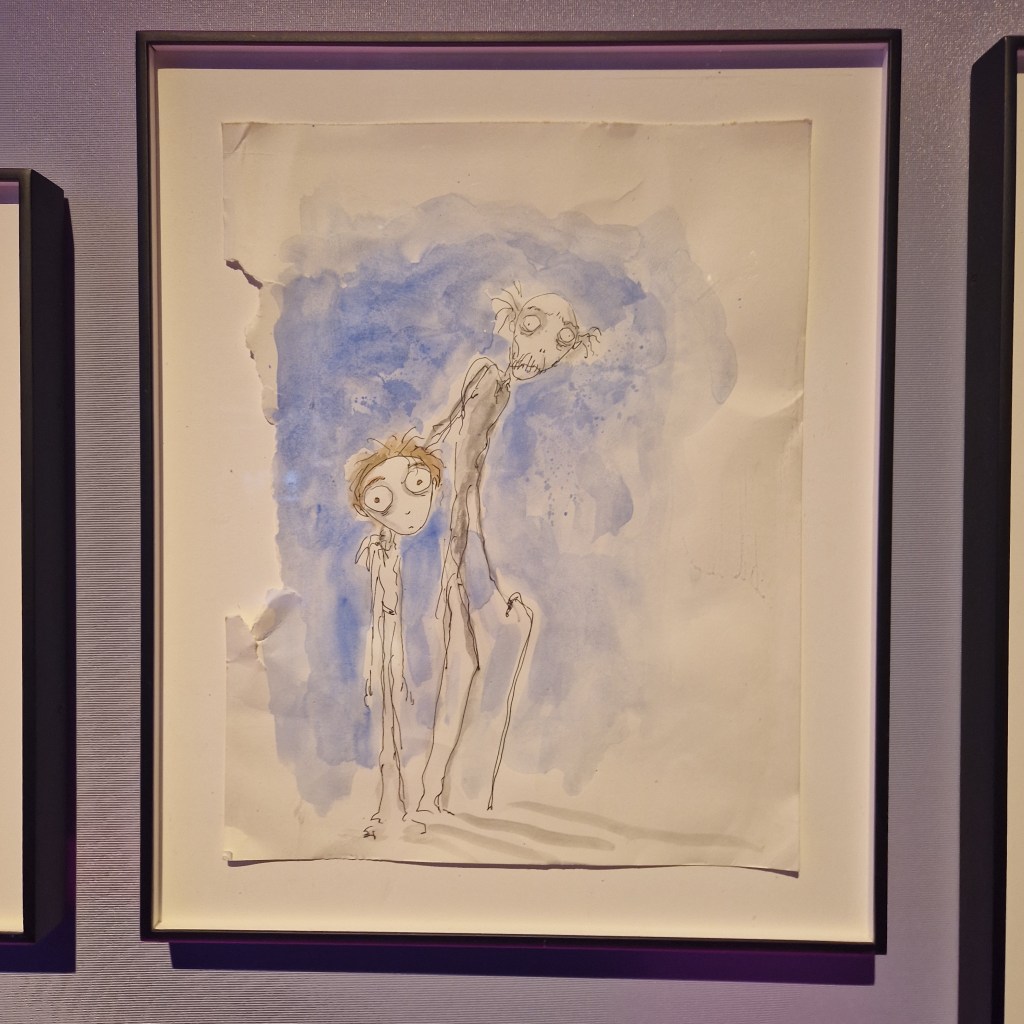

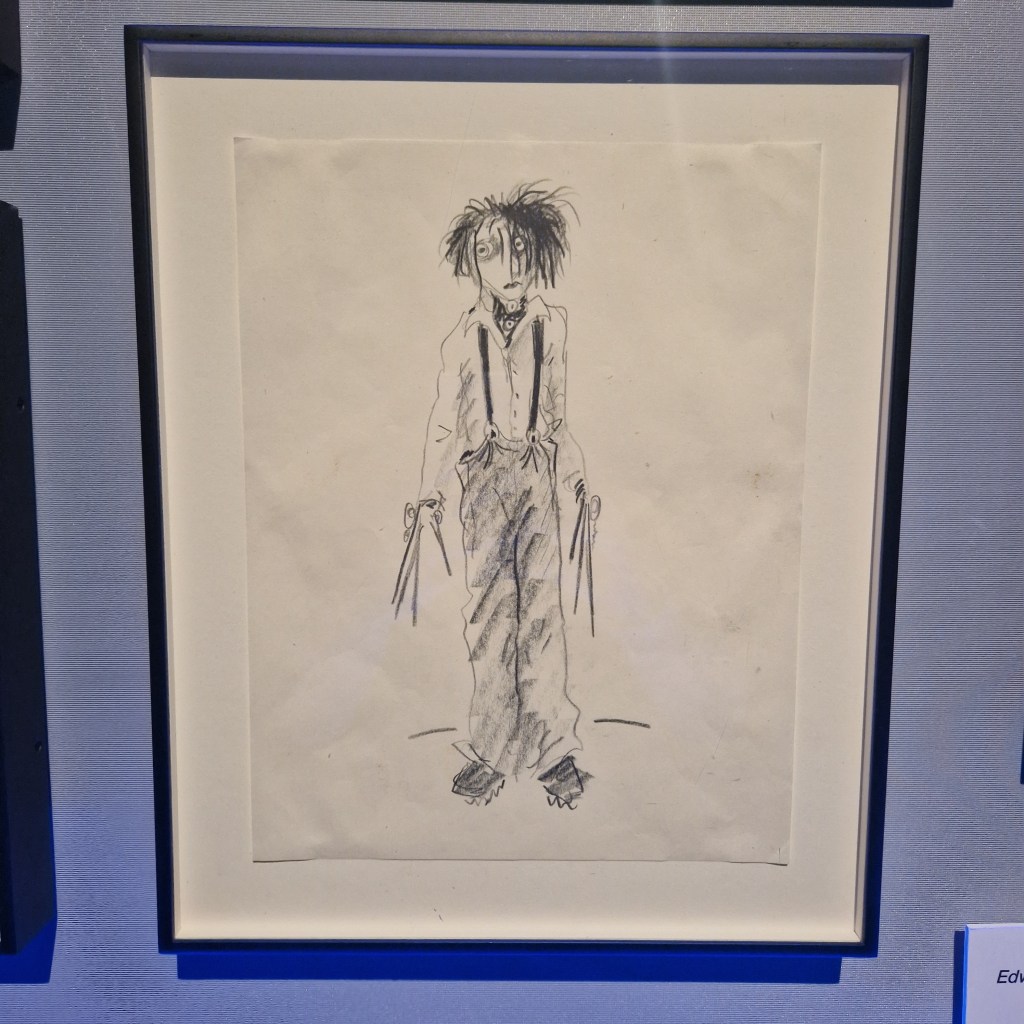

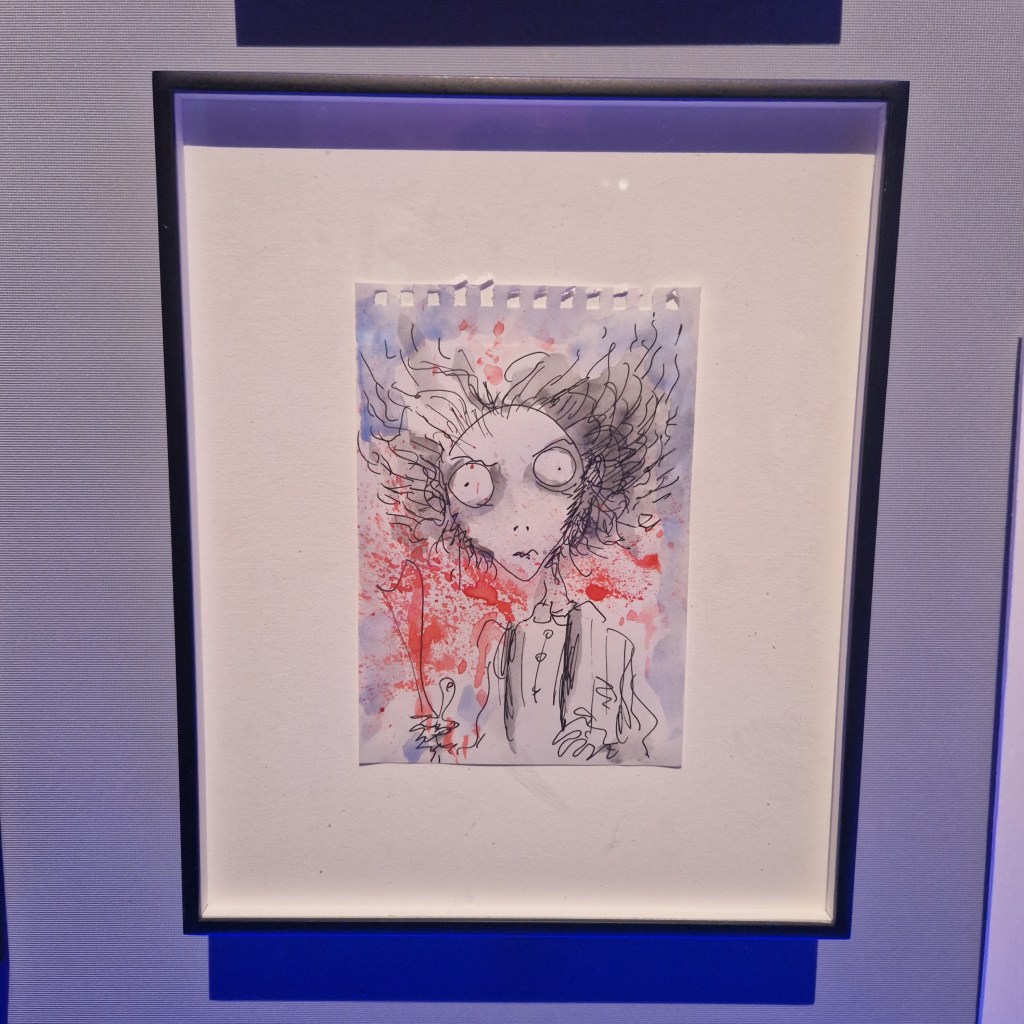

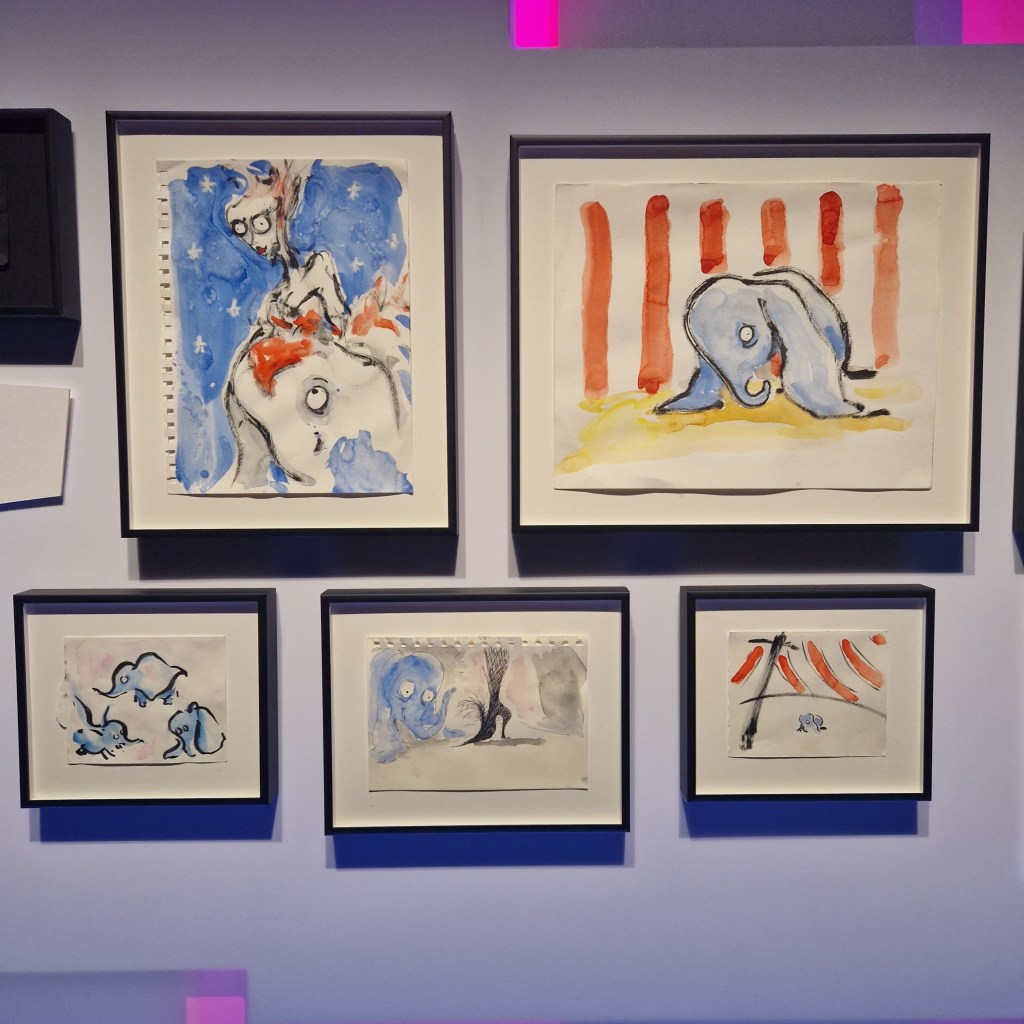

Past the towering timelines and cinematic relics, the exhibition opened into something quieter. Something more intimate. A room filled with sketchbooks and drawings on napkins. Dozens of them.

I thought back to my own sketchbooks over the years. How utterly uninspiring they felt in comparison. That isn’t just me being modest. Burton’s work isn’t comparable to anyone else’s. Every character, every monster bears his unmistakable stamp. Crooked, intriguing, unsettling. His visual language has remained unmovable, untouched by trend or compromise.

These weren’t just drawings. They were emotional blueprints. Each one whispering something half-formed, half-felt.

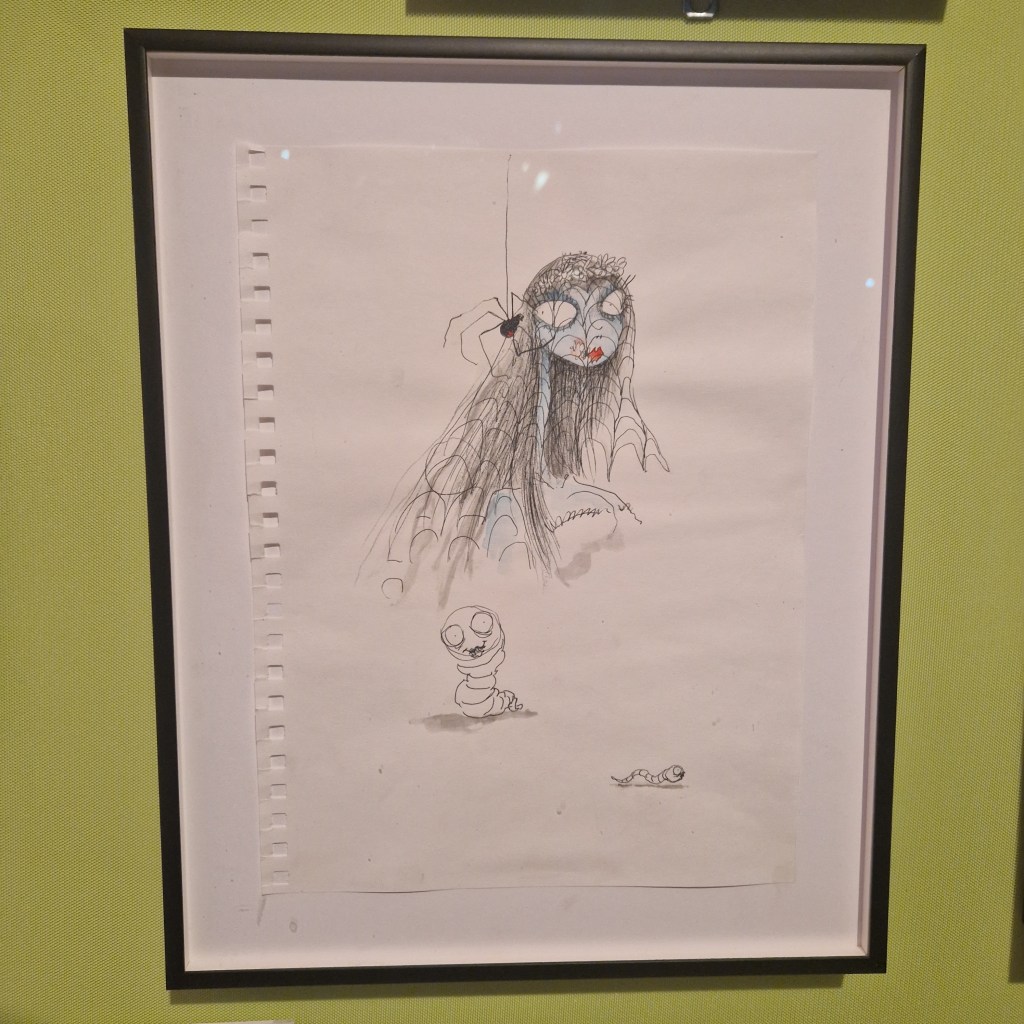

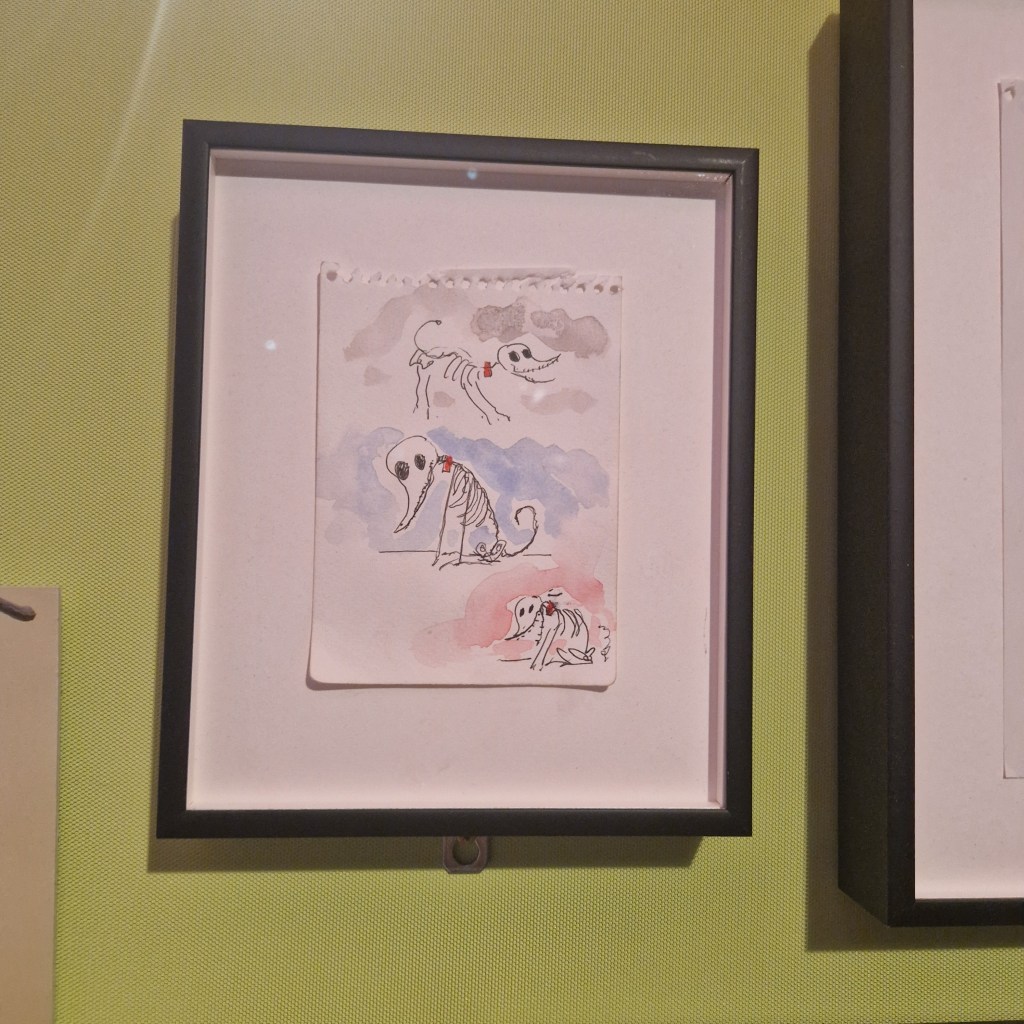

They weren’t polished storyboards or production-ready designs. These were fragments of his imagination. Scribbles on hotel stationery, napkins, tear-away notepads. Creatures half-formed. Eyes too large. Limbs too long. Women with cobwebbed hair and sorrowful grins. A beautiful perfect collection of misfits.

It felt less like looking at art and more like eavesdropping on a mind that never stops sketching. Burton once said,

“Drawing is my way of processing the world. I don’t always know what I’m thinking until I sketch it.”

In that room, you could see the repetition, the motifs that haunted him. The almond-shaped eyes. The crooked architecture. The lonely figures. It wasn’t just a style; it was a language. And we were being allowed to read it.

From Sketches to Screen

Just beyond the sketchbooks, the exhibition shifted again, this time into something three-dimensional.

They stood in glass cases, each one pulled from Burton’s drawings and given form. You could see the translation, lines becoming limbs, expressions solidifying into something you could walk around.

And yet, they were exactly as intended. As if someone had breathed life into the sketch and it simply stood up and stepped off the page.

Some were familiar: aliens from Mars Attacks!, characters from The Nightmare Before Christmas and even a few Oompa Loompas. Others felt more obscure, like prototypes from a dream that never quite made it to screen.

Burton’s sculptures don’t invite comfort. They hold their shape, but not their peace. And in that room, surrounded by them, it was clear: his world isn’t just drawn, it’s built.

Character in Cloth – The Costumes

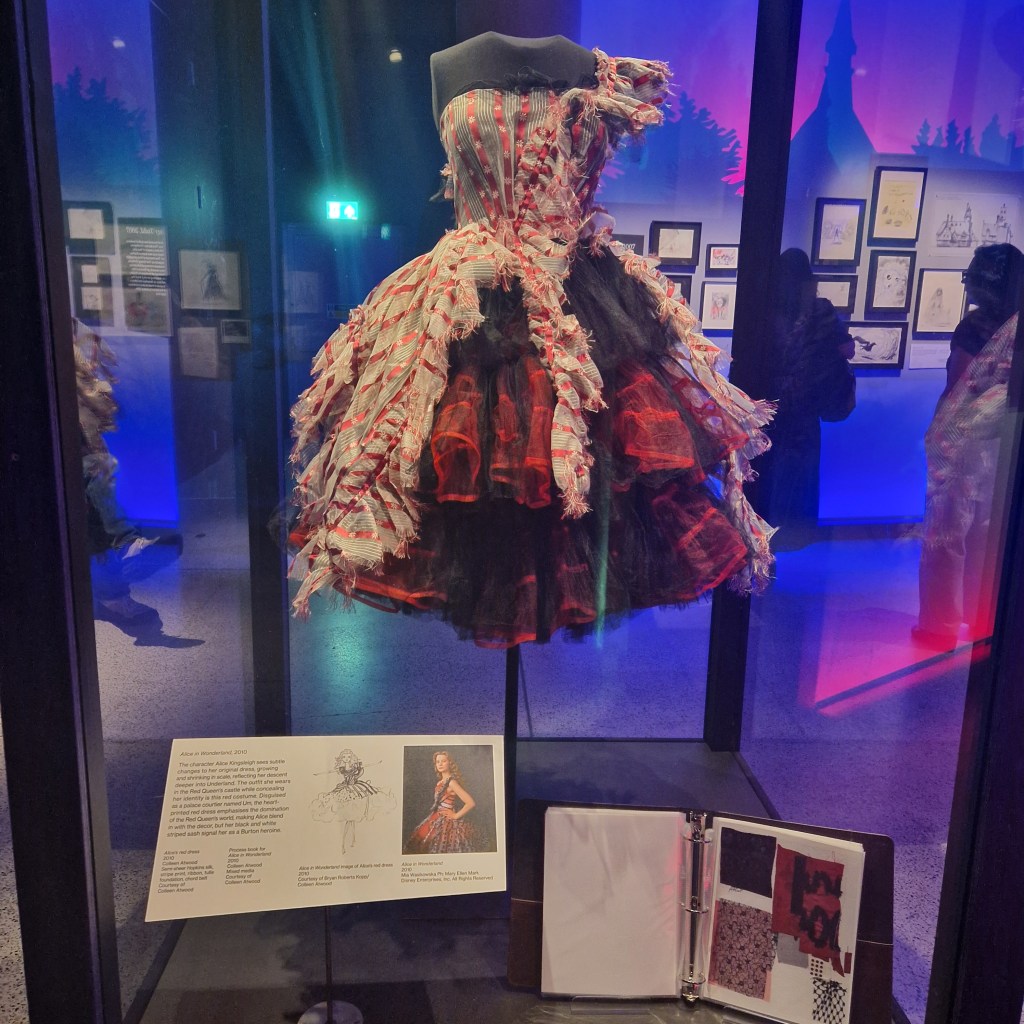

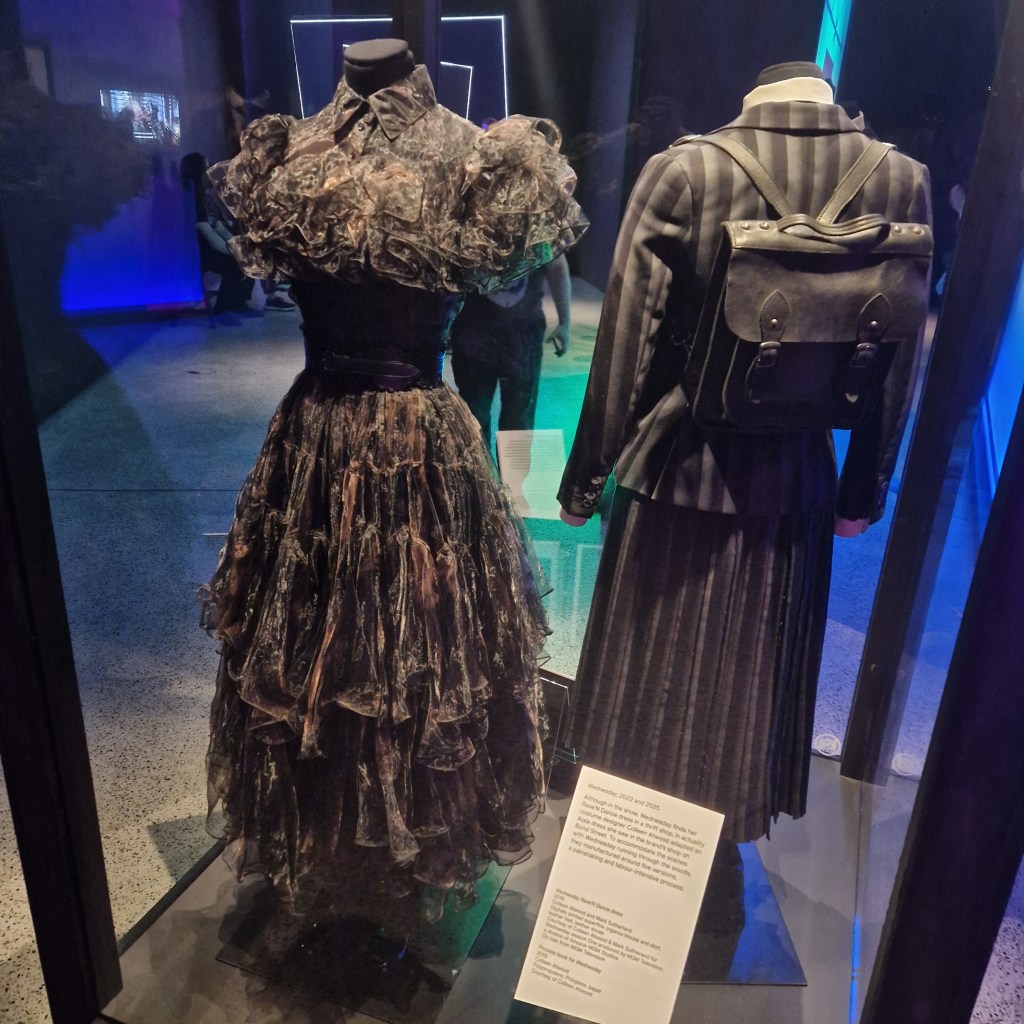

The costume room felt different. Less eerie, more deliberate.

Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman suit from Batman Returns (1992) stood taut and glossy. A second skin for a character who refused to be softened.

Nearby, Wednesday Addams’ Rave’N dance dress from the 2022 Netflix series hung with quiet defiance. Black chiffon, layered and sharp.

These weren’t just costumes. They were design choices that shaped how we read the characters before they spoke. Burton’s long-time collaborator, Colleen Atwood, understood this. Her work doesn’t decorate. It defines.

In this room, the fabric did the talking. And every stitch had something to say.

The Architect of Oddity

Tim Burton’s work doesn’t ask to be liked. It doesn’t chase approval. And yet, it’s adored and loved by millions of people around the world.

It stands crooked, precise, and unmistakably his.

Walking through the exhibition, I wasn’t just revisiting familiar characters. I was seeing the scaffolding behind them. The sketches, the sculptures, the stitched silhouettes. Each piece a small part of a larger story. A language of emotional shorthand built over decades.

And maybe that’s what makes his work so enduring. It doesn’t explain itself. It just exists.

For those of us who’ve always felt slightly out of place, it’s not just art. It’s recognition. It’s home.

Closing Remarks

The World of Tim Burton closed its doors on 26 May 2025, marking the end of its only UK showing and the final stop on a decade-long world tour.

I know not everyone could make it. So I hope this letter from the House offers you a small way in. Something strange. Something familiar. Something that stays.

Leave a comment